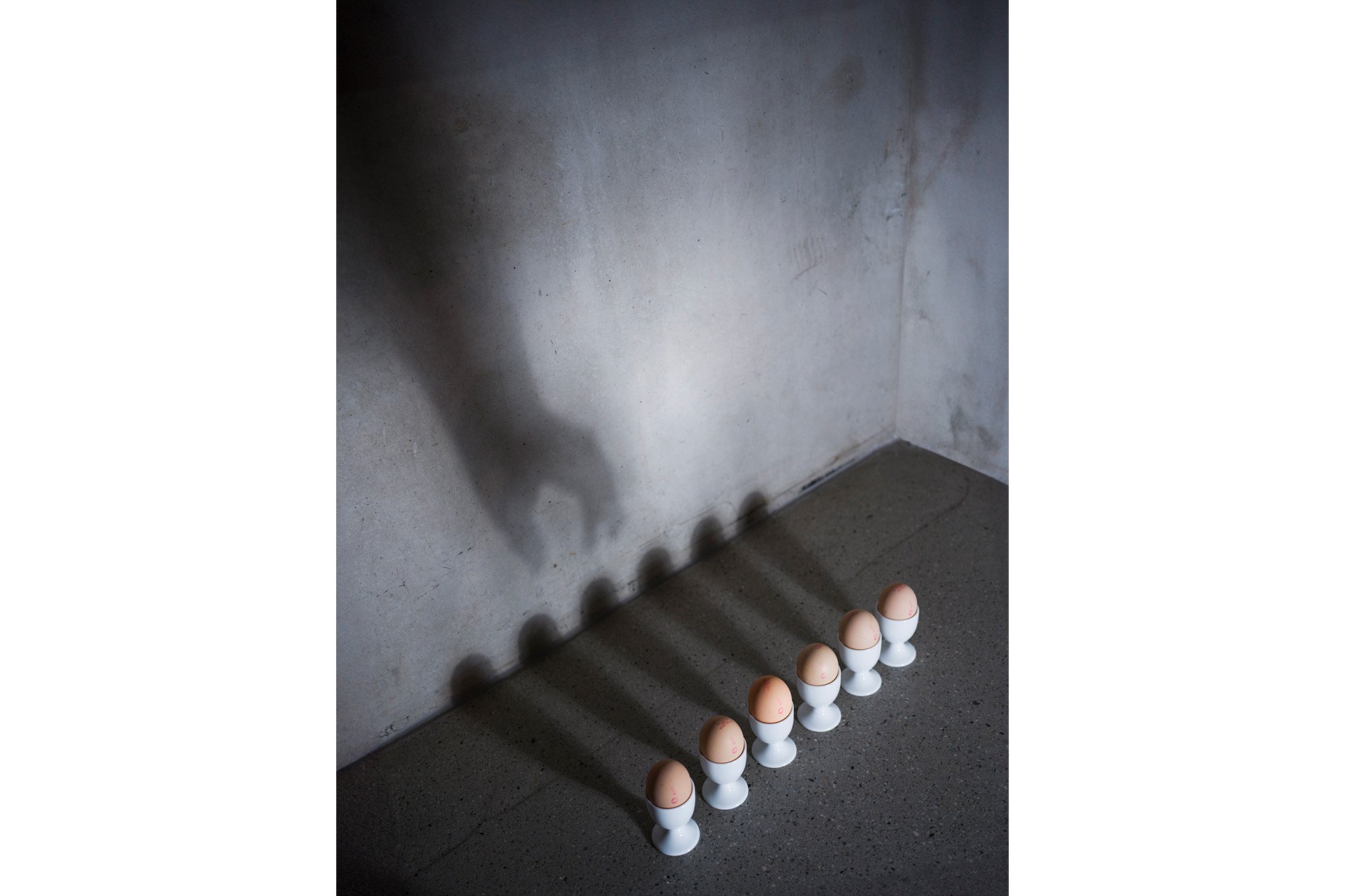

Behind the image: “Shadows and eggs”

Project Summary

The images in ‘31 explore social and political parallels between the present and the late 1920s and 1930s.

The project’s limited-edition archival pigment prints measure 31 x 42 cm (12.2 x 16.5 inches).

caption to “Shadows and Eggs”

"Shadows and Eggs" explores uniqueness versus uniformity using the egg, like many photographers of the Bauhaus movement did in the 1920s. The contemporary depiction links historical and modern eras of mass production. However, the photograph goes beyond the question of perception. It also comments on the situation of women, who are unwilling to fulfil the societal and political expectations of child bearing. The number of eggs references to one of Hitler’s speeches in 1936. In his address, the country's leader made it clear, that in his regime's view, mothers are more deserving than women with a career and both should be treated according to their worth. This view is echoed by many leaders of today.

Shadows and Eggs - 2023

Copyright: Zsofia Daniel

Shadows

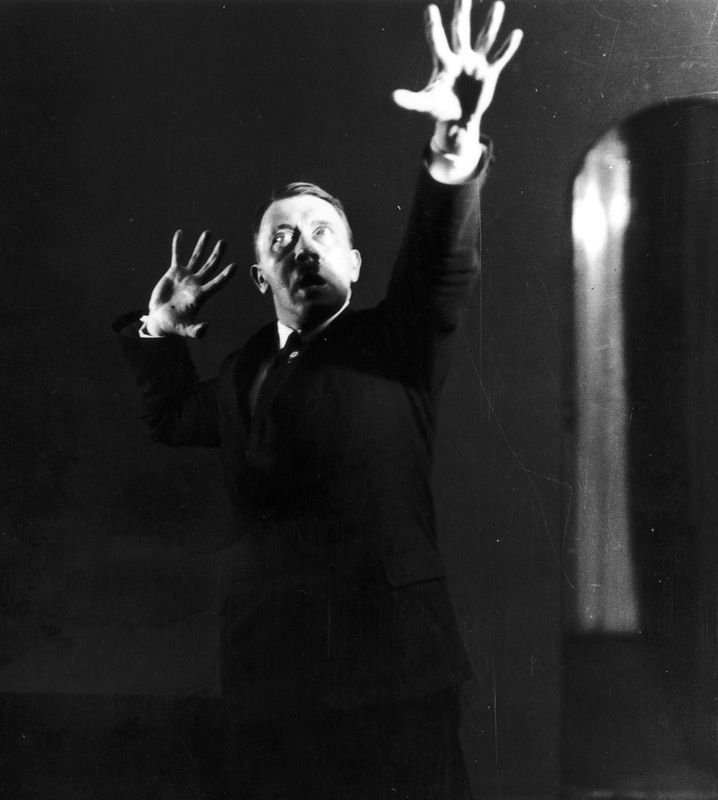

In "Shadows and Eggs," the shadows and colours are not just visual elements but are integral to the image's narrative, echoing the use of shadow to convey deeper meanings about identity, perception, and reality in Schad’s and Hoffmann's works. Much like the shadows in Hoffmann's 1925 photograph of Adolf Hitler, elevating the scene to a display of power and manipulation and in Schad’s 1928 painting of Dr. Haustein drawing attention to emotional detachment and fractured human relationships, the mentioned elements give deeper meaning to the photograph.

Although the shadows of the eggs are uniform, the hand of the unidentified higher power reaches for the one with a slightly richer colour than the others. Besides this act, the shadows transform the eggs and the unknown hand into something more significant and emotionally charged.

The six eggs in the image also reference to Hitler’s speech to the National Socialist Women’s Organisation on 11th September 1936. In this address, the Nazi leader described his vision of women’s role in German society:

“I am often told: You want to push women out of all professions. I just want to give her the widest possible opportunity to get married and to be able to help found a family of her own and to be able to have children, because then, and this is my conviction, she will naturally benefit our people the most.

“Because that is clear, and you must understand this from me:

“If I have a female lawyer in front of me today, and she can still do so much, and next door a mother with five, six, seven children, and all the children are quite healthy and have been well brought up by her, then I would like to say, from the eternal point of view of the eternal value of our people, the woman who can have children and who now has had them, and who has now brought them up and who has given our people life into the future again, has achieved more. She did more! She helps to avoid the death of our people.”

Hitler rehearsing his speech in front of the mirror by Heinrich Hoffmann (1925)

Eggs, Eggs and More Eggs

For 1920s photographers such as Aenne Biermann, Hans Finsler and others who were part of Germany’s Bauhaus art movement, the egg was an object of fascination.

The same was true for amateur photographers. As cameras became easier to carry around and commercial film processing made available, many of them found a new excitement in looking at the world through the lens. To fulfil their curiosity and help them understand a camera’s ability to capture light and shadow they searched for a “standard object” to photograph.

This basic form had to be

“white, so that no nuances of colour could influenve the effect of light and shadow; it would have to be have a very simple and universally familiar form, so that everyone could recognise the relationship of the photograph to this form; it would have to be had cheaply in any amount of uniform examples; and it would possibly have to be a natural product, because all artificially created things depend on the time and method of their production.”*

In their search for this standard object, photographers found the egg. Their images of eggs challenge our perceptions about the natural and the man-made, about an original versus a reproduction, and about uniqueness versus uniformity.

* Hans Finsler: Die Ei und die Fotografie, 1961